The Art of Building and Selling

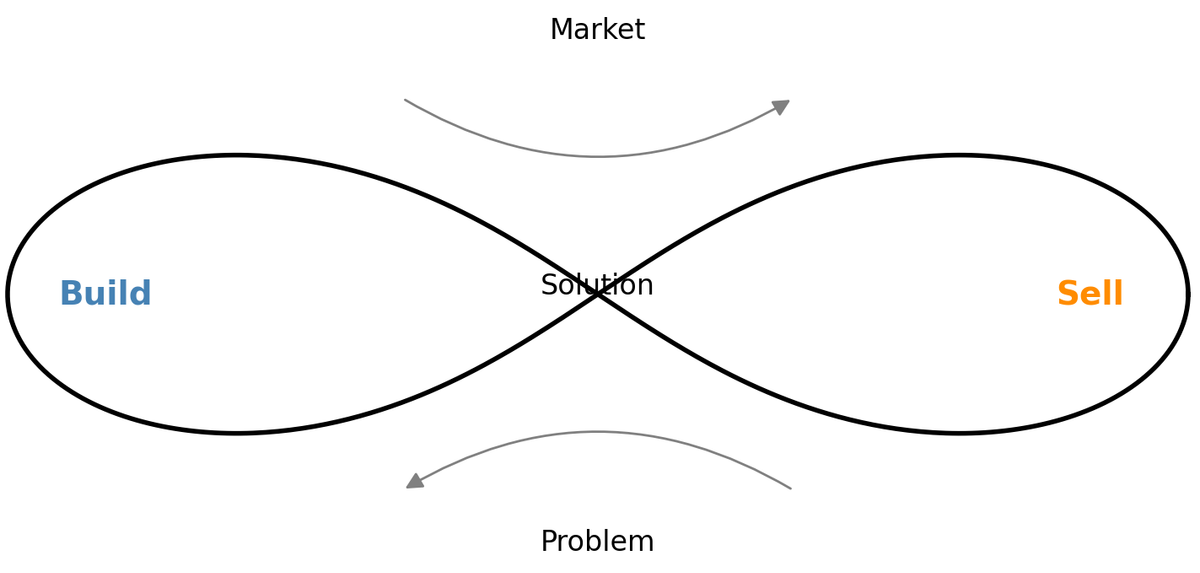

Most founders obsess over either building or selling. The truth? You need both working together in a loop. Think of your startup as an infinite cycle: building feeds selling, selling feeds building. The faster that loop spins, the closer you get to product-market fit.

Unifying Building and Selling

Startups must unify building and selling into a continuous cycle. We can imagine an “infinite venture loop” with a Build lobe on the left and a Sell lobe on the right, feeding into each other.

On the Build side, a startup cycles through these stages:

Hypothesize → Pretotype/Build → Ship → Instrument (measure) – this is the product development flow from idea to live product.

On the Sell side, the cycle is:

Position → Prospect → Close → Onboard → Retain/Expand – essentially the go-to-market and customer lifecycle.

At the center where they intersect is a “Learning hub” that represents the qualitative and quantitative insights (user interviews, telemetry, pricing feedback) that inform what to build next. The entire loop is governed by three ways discussed below:

Flow (Build-Measure-Ship)

In a startup, 'flow' refers to the process of moving from market discovery and ideation to placing a product in customers' hands as quickly as possible. The goal is to optimize the time from hypothesis to live product, your idea-to-production lead time. The quicker you can test an idea in the real market, the sooner you discover its true value.

Lean Startup philosophy echoes this: launch early and iterate. Paul Graham advises startups to launch fast because until real users are trying your product, “you haven’t really started working on it” you’re just guessing .

A mediocre first version tested with real users beats a perfectly planned idea that never sees the light of day. Reducing batch size is essential: instead of building a massive, polished product over many months, successful startups break work into small, releasable increments. Most begin with a Minimum Viable Product (MVP)—the smallest functional version of an idea that can test a hypothesis. For instance, a startup can spend eight months building what they believed was the perfect app, only to discover upon launch that competitors had already seized the market opportunity.

By starting with small, incremental releases, startups can respond more rapidly to market demands and feedback.

“Make sure you are building The Right It before you build It right.” ~ Alberto Savoia

In other words, validate the idea’s market fit before investing in perfection. Pretotyping techniques (like fake landing pages, Wizard-of-Oz simulations, manual concierge services) let you deliver some form of your solution to customers in days to gauge interest.

This emphasis on rapid, low-cost validation maximizes flow through the build loop, and you only fully build things that have proven demand.

The goal is a fast idea-to-live cadence so you can learn quickly.

Feedback (Market Signals → Build).

The counterpart to fast flow of features is a strong flow of feedback from right to left, from customers and the market back into product development. In our venture loop, every stage on the Sell side generates learnings that should loop back.

For example, how people respond to your Positioning and messaging tells you if you’re targeting the right value proposition. During a recent prospecting call, a potential customer mentioned, "I love the concept, but the integration seems too complex for our existing systems." This kind of direct feedback highlights unmet needs and obstacles we may not have considered.

Prospecting and sales calls yield additional insights into objections and unmet needs. Onboarding new users reveals where your product is confusing or failing to deliver expected value. Ongoing usage patterns and support interactions highlight what customers love, what confuses them, and what they wish your product did. A culture of feedback means actively listening to these signals and acting on them quickly.

This requires startups to “get out of the building” and talk to users. Steve Blank’s first rule of customer development is that insight won’t come from inside your office. Founders need to be out interviewing customers and observing behavior in the wild. Blank admonishes startups to focus less on internally driven ideas (“design and sell” in a vacuum) and more on understanding who the customer is, what they need, and how you can help.

That means continuously soliciting feedback: through user interviews, surveys, usability tests, and by instrumenting your product to collect data. Modern product teams embed analytics (e.g. funnel metrics, feature usage) and implement feedback loops like NPS surveys to amplify the voice of the customer.

The faster and more frequently this feedback flows, the quicker you can correct mistakes or add features that matter. For a startup, that might mean doing weekly customer calls, daily checks of usage dashboards, and very short cycles between identifying an issue and shipping an improvement.

For example, early-stage SaaS companies often have a public changelog with fixes and tweaks shipped almost every day in response to user feedback. Embracing feedback also implies a blameless culture on the business side: startups should treat an experiment that decreased signups or a sales approach that failed as learning opportunities, not failures of individual people. The goal of feedback is learning, not assigning fault. By rapidly cycling customer insight back into the product, a startup ensures it is building what people actually want and will pay for.

“Make something people want.” ~ YC’s mantra

Continual Learning and Experimentation

The third principle ties it all together. A startup must continually learn and improve, across both product and go-to-market. This means running many cheap experiments, not betting the company on one big plan. To turn this philosophy into a repeatable habit, founders should establish a regular cadence for experimentation.

For example, they could dedicate Monday mornings to framing new hypotheses and Thursday and Friday afternoons to shipping and measuring results. This schedule encourages a systematic approach to learning and ensures that new insights are consistently gathered and applied.

Eric Ries’s Lean Startup method explicitly encourages a Build-Measure-Learn loop, which is just another formulation of continuous experimentation. In practical terms, this entails working in small batches with frequent iteration. As Ries illustrates, small batches let you discover problems sooner and adapt. When you do things in tiny increments, whether deploying a tiny code change or testing a single ad, you get feedback fast (Did it work? Did it break something?). If an idea is going to fail, you’d rather fail on a small scale next week than on a grand scale next year.

“Working in small batches ensures that a startup can minimize the time, money, and effort that ultimately turn out to have been wasted”.

Startups that learn fastest win because they can course-correct before running out of resources. This is crucial given what Savoia calls the Law of Market Failure: most new product ideas will fail in the market even if excellently executed .

In other words, failure is the default in innovation so you must design your process to allow lots of “failed” tests without derailing the company. That translates to rapid, low-cost experiments: A/B test that new pricing page, run a 2-week trial in a niche market, spend R500 on ads to see if anyone clicks.

A probe for signal before fully committing. A culture of learning also values retrospectives and root-cause analysis. When an experiment or release doesn’t go as hoped, the team asks “What did we learn? What will we do differently?” rather than seeking someone to blame. And when something succeeds, they also ask why and whether it’s repeatable.

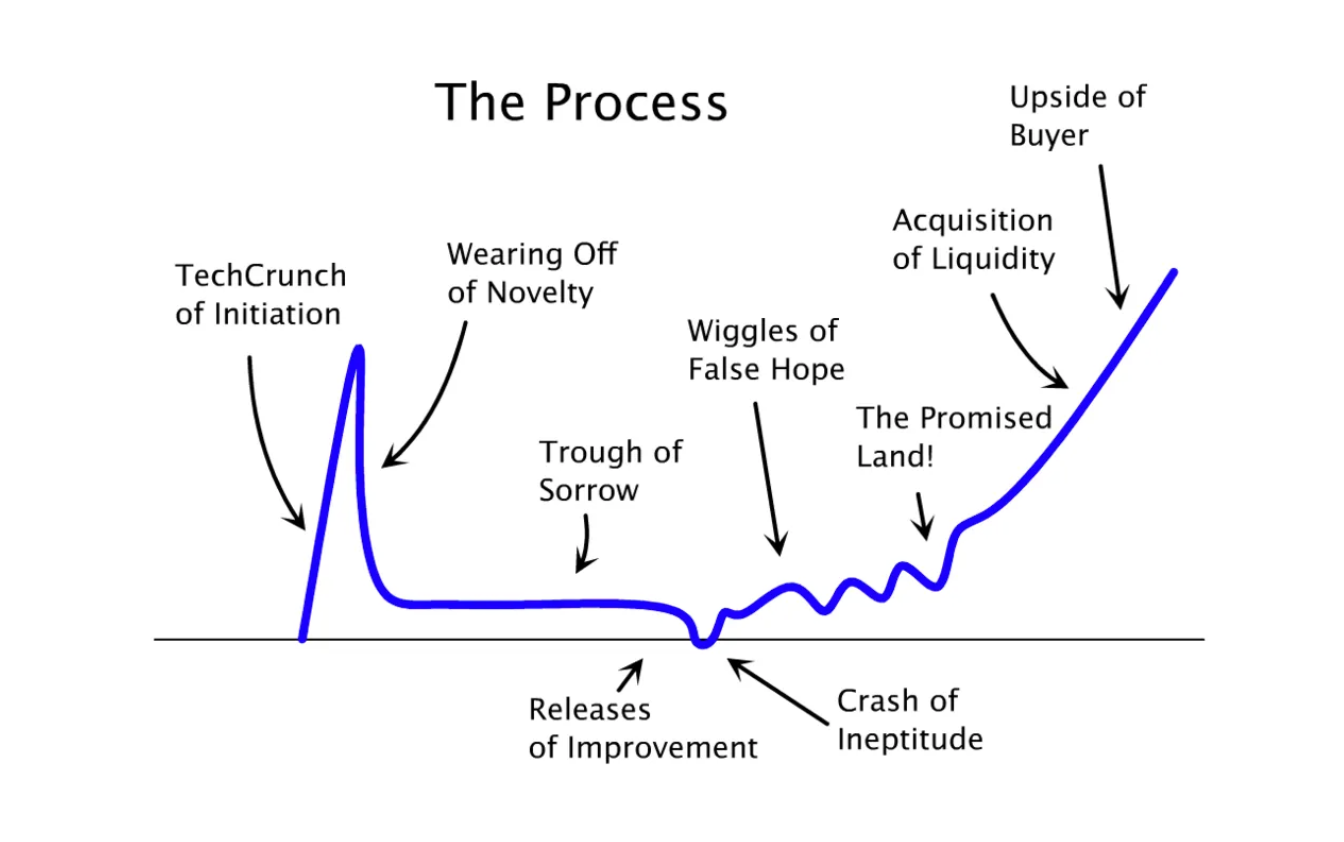

It’s worth noting that persistence is a part of continual learning as well. In startup lore, the “Trough of Sorrow” describes the long, hard period after initial excitement wears off, when growth is slow and everything feels like a grind.

Nearly every startup hits this trough, and only those with a learning mindset make it through. As investor Marc Andreessen quipped, the only thing that causes startups to fail is running out of money and Paul Graham observed this is often because they didn’t find product/market fit in time, or the founders gave up too early.

The antidote is fast iterations and resilience: keep testing changes to find something that moves the needle (a feature that boosts retention, a pivot to a more promising market) before the clock runs out.

Many famous startups only succeeded on iteration #3 or #4 of their concept. For example, Slack emerged from the ashes of a failed game after Stewart Butterfield’s team noticed their internal messaging tool was the most valuable thing they had, it took two major pivots (failing and learning each time) to arrive at Slack’s wildly successful product.

Instagram was a pivot from a cluttered app (Burbrn) that wasn’t catching on and the founders learned from user data that photo sharing was the popular feature, so they stripped everything else away and relaunched just around photos (a classic small-batch experiment).

These stories highlight continual experimentation: trying multiple approaches, listening to users, and doubling down on what works.

In summary, a startup should operate as an infinite loop of Build ↔ Sell. The left-to-right flow (build -> deliver) must be fast and frequent, and the right-to-left flow (market feedback -> learn) must be constant and amplified.

Surrounding the loop are key callouts for success: reduce batch size, automate where possible, talk to users, measure outcomes. By embracing those, startups create a virtuous cycle where product development and customer development reinforce each other continuously.

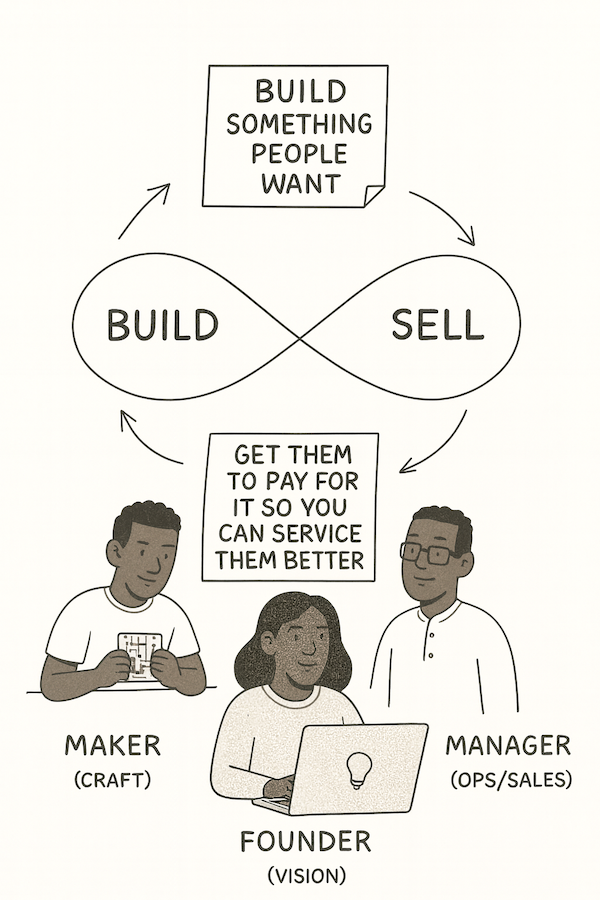

The Founder’s Role: Balancing Entrepreneur, Manager, and Technician

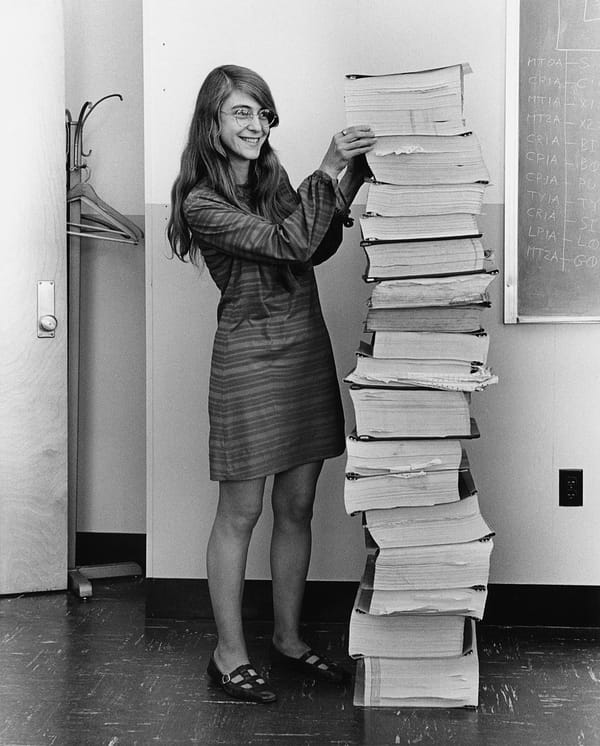

Implementing an infinite build-sell loop requires founders to wear multiple hats effectively. In Michael Gerber’s E-Myth framework, a small business owner embodies three personas: Entrepreneur (visionary), Manager (organizer), and Technician (doer).

For a startup founder, this translates to being the visionary driving new ideas (entrepreneur), the one building the product or executing the work (technician), and the one putting in place processes and systems to scale (manager).

It’s rare for one person to be naturally strong at all three, and indeed Gerber notes most people start a business as a Technician, meaning they have a particular craft or technical skill, and often spend too much time “in” the business rather than “on” the business.

For example, a brilliant software engineer founder (Technician) might focus 100% on coding the product but neglect talking to customers or formulating a go-to-market strategy.

This imbalance can doom the venture, because great code alone doesn’t guarantee a product people want or a way to reach them. Founders need to consciously balance the Builder and Seller roles, either within themselves or across a founding team. If you’re a deeply technical founder, you must “learn to sell”, not in the stereotypical sense of high-pressure sales tactics, but in the broader sense of understanding customers and how to persuade them to try/buy your product. That means investing time in the Entrepreneur role: setting the vision, crafting messaging, getting out in the field with customers, and hustling to close early deals.

Many technical founders have shared how they initially resisted or struggled with sales, viewing it as outside their comfort zone, but later realized that focusing on the customer’s problem is just as important as the code. In fact, one of the most important mindset shifts is going from being product-obsessed to customer-obsessed:

“If you want to build a business, you have to stop being obsessed with technology and start to focus on the customer and their problems.”

This doesn’t mean abandoning product quality; it means letting customer needs drive what you build. On the flip side, a business-savvy or sales-oriented founder must “learn to ship”. They might not write code, but they need to deeply engage with product development, embrace agile iteration, and perhaps acquire enough technical understanding to make product decisions and not overpromise beyond what can be delivered.

A classic example is the “hustler + hacker” co-founder model were one founder focuses on selling and the other on building. That can work well, but even in those pairs the best duos cross-pollinate (the builder spends time with customers and the seller gives input on product features).

A brand-new startup product is the epitome of an exploratory project: you often don’t know exactly what the customer wants, the technology approach may involve new tools (uncertain process), and you have limited people/money (resource constraint).

In an exploratory environment, the primary goal is to maximize learning and output given the unknowns, rather than strict adherence to a plan.

This means the Manager role for a founder is about enabling rapid iteration e.g. setting up an agile process, not a rigid Gantt chart; keeping the team focused on experimentation; and being ready to pivot.

Founders should heed this: if your project is exploratory (and almost all startups are), optimize for rapid learning over efficient execution of a fixed plan.

Put another way, in an exploratory startup, the Entrepreneurial role (vision and adaptation) must guide the ship through foggy waters, the Technician role (building product) must deliver iterative prototypes and increments, and the Manager role (organization) must create a structure that tolerates ambiguity, focusing the team on outcomes (like user engagement or revenue milestones) rather than detailed feature roadmaps set in stone.

Many early-stage startups now adopt OKRs or North Star metrics as management tools, precisely to keep the team aligned on learning goals and business goals rather than output of features.

For instance, a founder-CEO might set an objective to “validate a scalable customer acquisition channel by Q2”, a goal that forces collaboration between product (to build the necessary hooks or virality features) and marketing/sales (to experiment with campaigns), rather than siloing those functions.

In summary, the founder (or founding team) needs to constantly shift between modes: innovating, executing, and systematizing. Gerber’s key message is to not get trapped solely in the Technician’s mindset, in other words, working in the business (coding, designing) without also working on the business (strategy, sales, systems).

Founders who successfully balance these roles either individually or collectively are far better equipped to drive the continuous build-sell loop. A practical tip is to literally allocate time for each: e.g., spend mornings on product (Technician), afternoons on customer calls and strategy (Entrepreneur), end of week to review team process and metrics (Manager). And as the company grows, hiring or delegating can fill gaps e.g. bring in a product-oriented CTO if you’re business-heavy, or a growth lead if you’re engineering-heavy. The end goal is a leadership that integrates product and market seamlessly, ensuring neither side of the loop is neglected.

Treat your startup like an infinite loop of hypothesis, experiment, feedback, and insight, encompassing both product and market.

To transform this concept into action, challenge yourself: what can you ship tomorrow, no matter how simple or small? Could it be an MVP of a new feature, or a brief user survey designed to capture early feedback? By embracing action, you'll not only enter the loop more quickly but also accelerate your learning and adaptation process.

Measure both how fast you ship and how much customers love and use what you ship. The payoff is a startup that can swiftly adapt to find product-market fit and then continuously evolve to expand that fit, essentially achieving continuous innovation. It’s like having dual engines firing in sync: the Build engine and the Sell engine, propelling the venture forward.

Founders who get both engines revving and steer using data are well on their way to building an enduring, scalable business in the mold of the greats of the last 15 years.

By uniting building and selling in an infinity loop, you ensure that you’re not just doing things right, but also doing the right things, faster than the rest.